As regular readers will be aware, the Tower Project has reached the First World War. In amongst the usual school textbooks, novels and religious tracts we are now finding a good number of handbooks on soldiers’ duties, military drill and tactics, firing muskets, fighting with bayonets, care of the wounded, prayers for the soldiers and much other war related material.

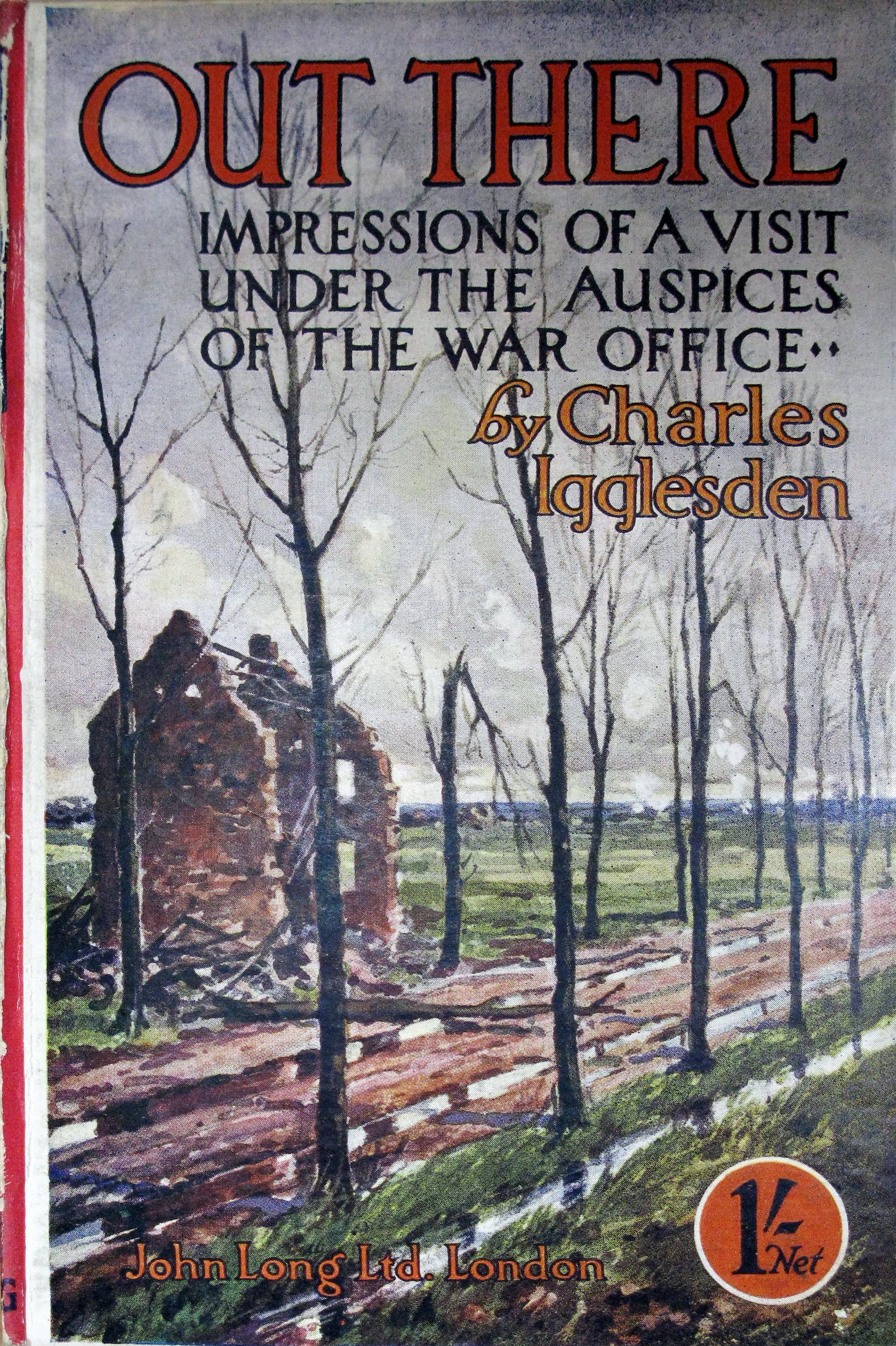

This week I also came across “Out there,” which is an account of a visit to Belgium and France in 1916, undertaken by Charles Iggleston on behalf of the British government [1916.6.617]. The book is described on the spine as “A visit to the Front under the auspices of the War Office, thrillingly and graphically described.” Naturally, it has strong patriotic overtones but at the same time it does give a flavour of how life was for the British Army of the day, in one small section of the war.

The author is full of admiration for “Tommy,” the British soldier: “dodging death at every hour of his life, he sticks to his work in grim earnest, with sublime devotion, overcoming all difficulties and obstacles, cheerful throughout, and with a fixed determination to win through in the end.”

The infantryman, he observes, “must needs bear the brunt of the fighting … all day and all night the infantryman is under fire so long as he is on duty, but in the mad rush of battle, the brunt of the fighting falls on him in a conspicuous degree. He it is who rushes from his trench in the attack across the open, swept by a hurricane of fire from machine guns. Only those who have seen No Man’s land between the opposing trenches can have any idea what this danger zone is like.”

The greatest everyday danger would appear to have been from the almost constant shelling, but the soldiers’ approach to them seemed almost blasé, perhaps because there was not much one could do to avoid them. Iggleston describes walking down an open track with a subaltern, who seemed unconcerned at shells flying overhead, save for commenting, “This is a bit dangerous.” He does then go on to explain the differences between “theirs” and “ours” and to say that one only needed to look out if the “whizz” became lower and lower…

This had its effect on the countryside “as many a blackened wall, many a roofless house, many shattered windows proclaim.” Probably, we have all seen the photographs of this land where “traces of fierce fighting are everywhere – a bit of shattered trench, the severed trunk of a lonely tree, odd strands of telephone wire, and twisted bundles from destroyed entanglements … a spot that has been fought over and over again till the soil must have become sodden with blood.”

This had its effect on the countryside “as many a blackened wall, many a roofless house, many shattered windows proclaim.” Probably, we have all seen the photographs of this land where “traces of fierce fighting are everywhere – a bit of shattered trench, the severed trunk of a lonely tree, odd strands of telephone wire, and twisted bundles from destroyed entanglements … a spot that has been fought over and over again till the soil must have become sodden with blood.”

The descriptions of the French people living in their ruined countryside are perhaps even more heart rending than the plight of the soldiers. Through a glass-less window, Iggleston sees an old peasant woman with a sad wrinkled face, sitting, knitting in the ruins of her cottage; having lost her two sons to the war and her two young grandchildren to a German raid. “No one hears the white-haired peasant woman talk. She just tends her garden, lives on the few vegetables it provides, and after that – knits, knits, knits.”

Many of the French homesteads had been knocked about by the shells, but their inhabitants continued to farm their ancestral lands, sometimes gathering their harvest within yards of the Germans lines, with shells falling around them. With all the able-bodied men away fighting, the ploughs are worked by “old men, who in England, would have been relegated to their children’s fireside, as incapable of doing another stroke of work … close by a farm cart was being drawn up a hill by a half-starved horse, an old women trying to help by pushing … while a little hunch-backed boy … added his strength to aid the struggling, panting horse. Such are the sights one sees while traversing miles and miles of French territory.”

Today is, of course, Armistice Day, marking the anniversary of the end of the Great War. None of the veterans survive now and increasingly the war is four or five generations removed and means only a few pages in a history book to many. It is hard to picture the scale of the war and the vast numbers of men who were killed or died of diseases “out there,” but all of us have ancestors who lived through that time. We should never forget.