Ever received an email asking you to help someone who was due to gain a large inheritance but just needed some funds (from you) to help claim it? You are not alone, many Victorians and Edwardians it appears did too. Ok not emails, but advertisements for help from those chasing claims were fairly numerous. They may not have been the same scams they are today but if their being labelled ‘spurious’ and ‘fanciful’ by contemporaries is anything to go by they appear as equally fruitless.

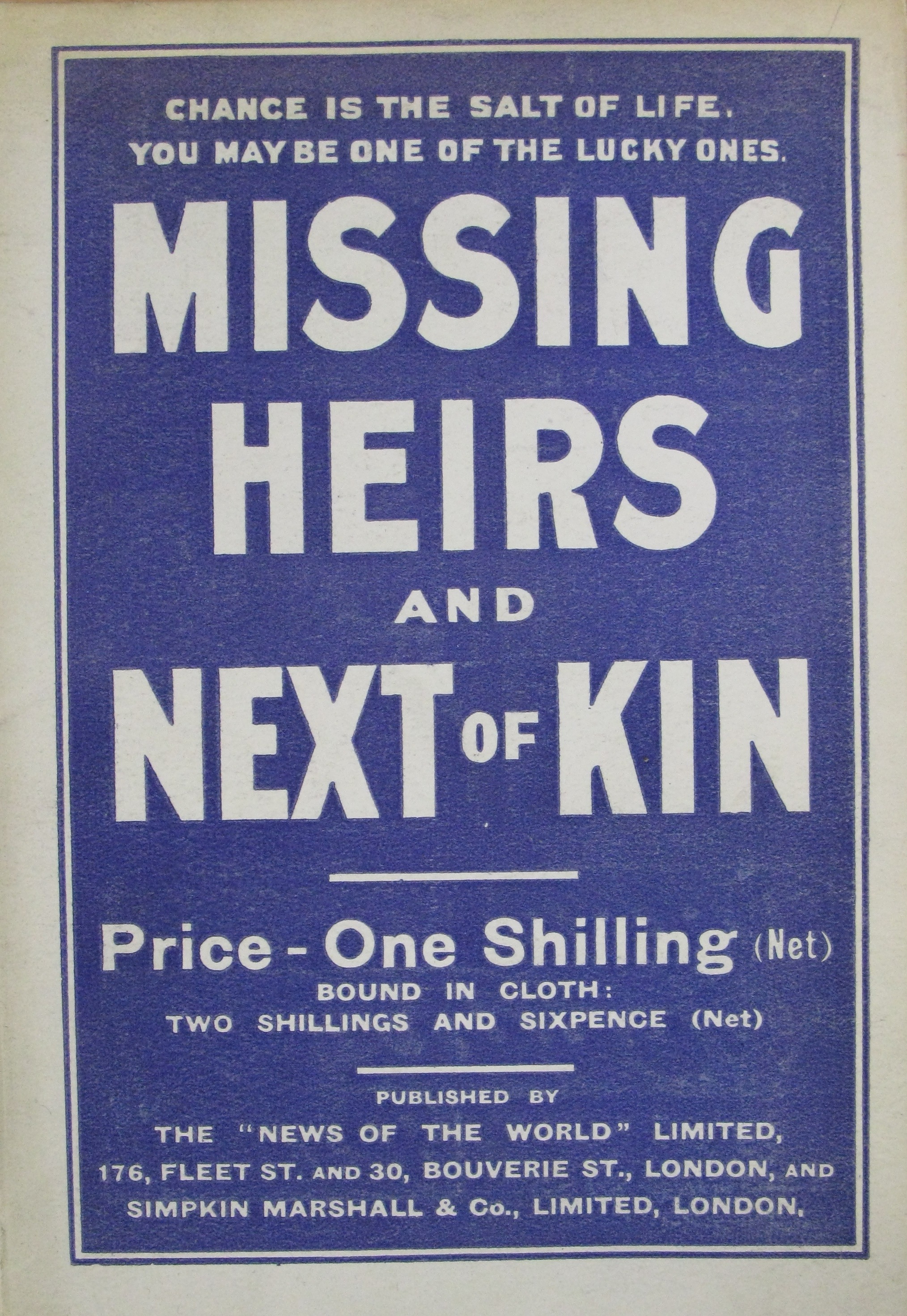

I have recently come across a book published by the News of the World, entitled ‘Missing heirs and next of kin’. This book contains lists and lists of missing people who were entitled to claim from their estranged dead relatives, acquaintances etc. On the one hand the idea of hundreds and hundreds of missing people is a weird concept, which certainly creeped me out, however on the other you can see where the hope of gaining and/or chasing a windfall came from.

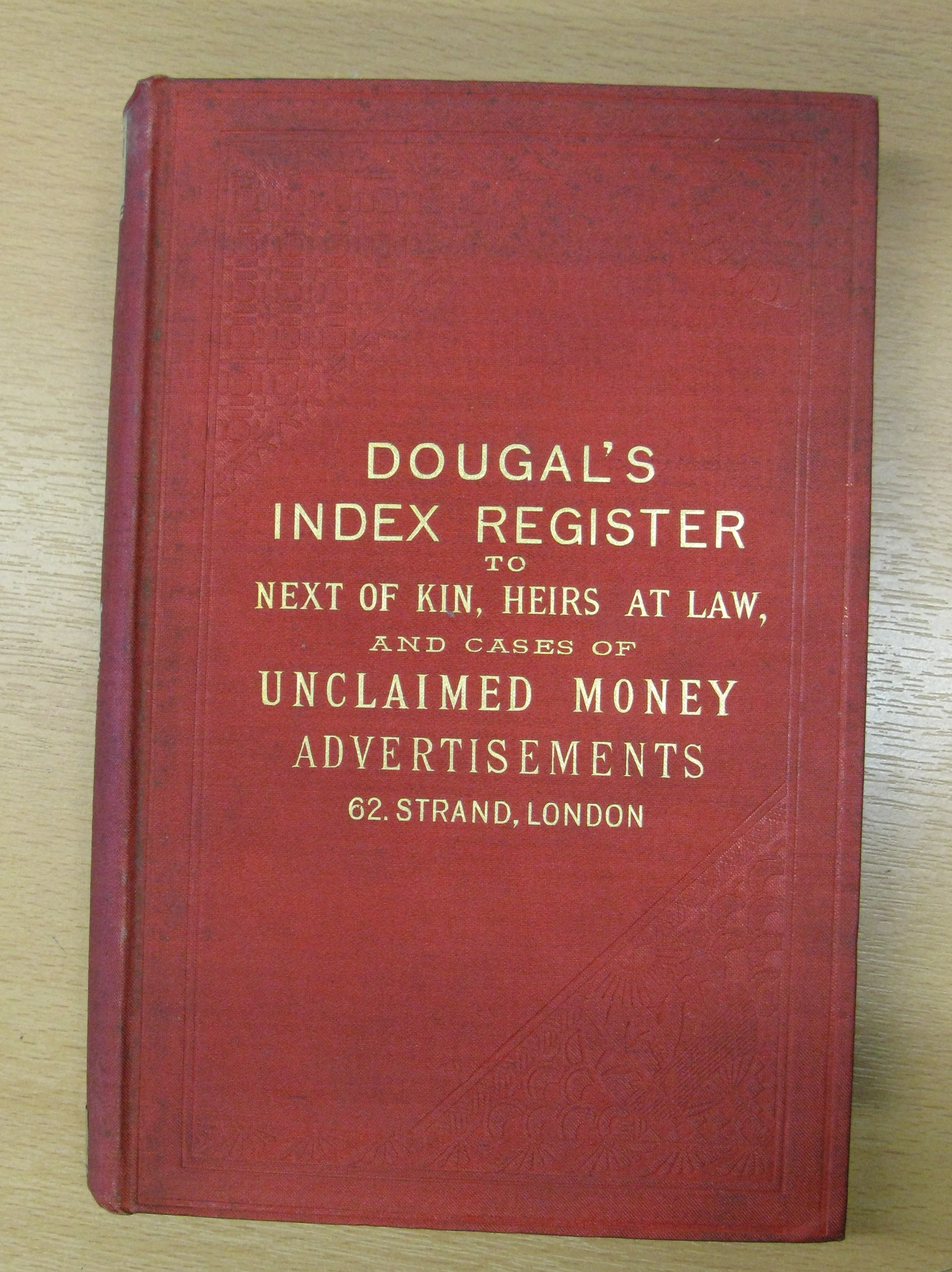

Fortune seekers’ first glimmers of hope were found among the “agony” columns of the press, which advertised assets held by the Crown, left by people who named no heirs. They may have also benefited from reading the London Gazette, which after the Chancery Fund Acts in 1872 was where the law courts listed dormant funds of those who could not be found.

My bo ok appeared to be a collection of agony columns and was fascinating. The amount of missing people was astounding and the information about them varied considerably. Some adverts were very specific: James Masterton, a spirit dealer’s assistant, was born in 1856 at 25 Salamander Street, Leith and was in Manchester during the Manchester Exhibition of 1887. Others were vague: James Upton of Stockport was a labourer, about 5 foot 7 with light brown hair, blue eyes and a fresh complexion. Hugh Connor formerly of Drumanmore was last heard of working as a builder’s labourer in or near Durham about 1881 but may have gone to America or Canada.

ok appeared to be a collection of agony columns and was fascinating. The amount of missing people was astounding and the information about them varied considerably. Some adverts were very specific: James Masterton, a spirit dealer’s assistant, was born in 1856 at 25 Salamander Street, Leith and was in Manchester during the Manchester Exhibition of 1887. Others were vague: James Upton of Stockport was a labourer, about 5 foot 7 with light brown hair, blue eyes and a fresh complexion. Hugh Connor formerly of Drumanmore was last heard of working as a builder’s labourer in or near Durham about 1881 but may have gone to America or Canada.

Another thing that surprised me was how global both the estates and claimants locations were: An Englishman named Russell, who resided at Folakara in Madagascar died in December 1909 leaving his estate to relatives, whereas George Edward Shelly of Bangkok, Siam known to have been in London in 1895 was called on to receive an endowment.

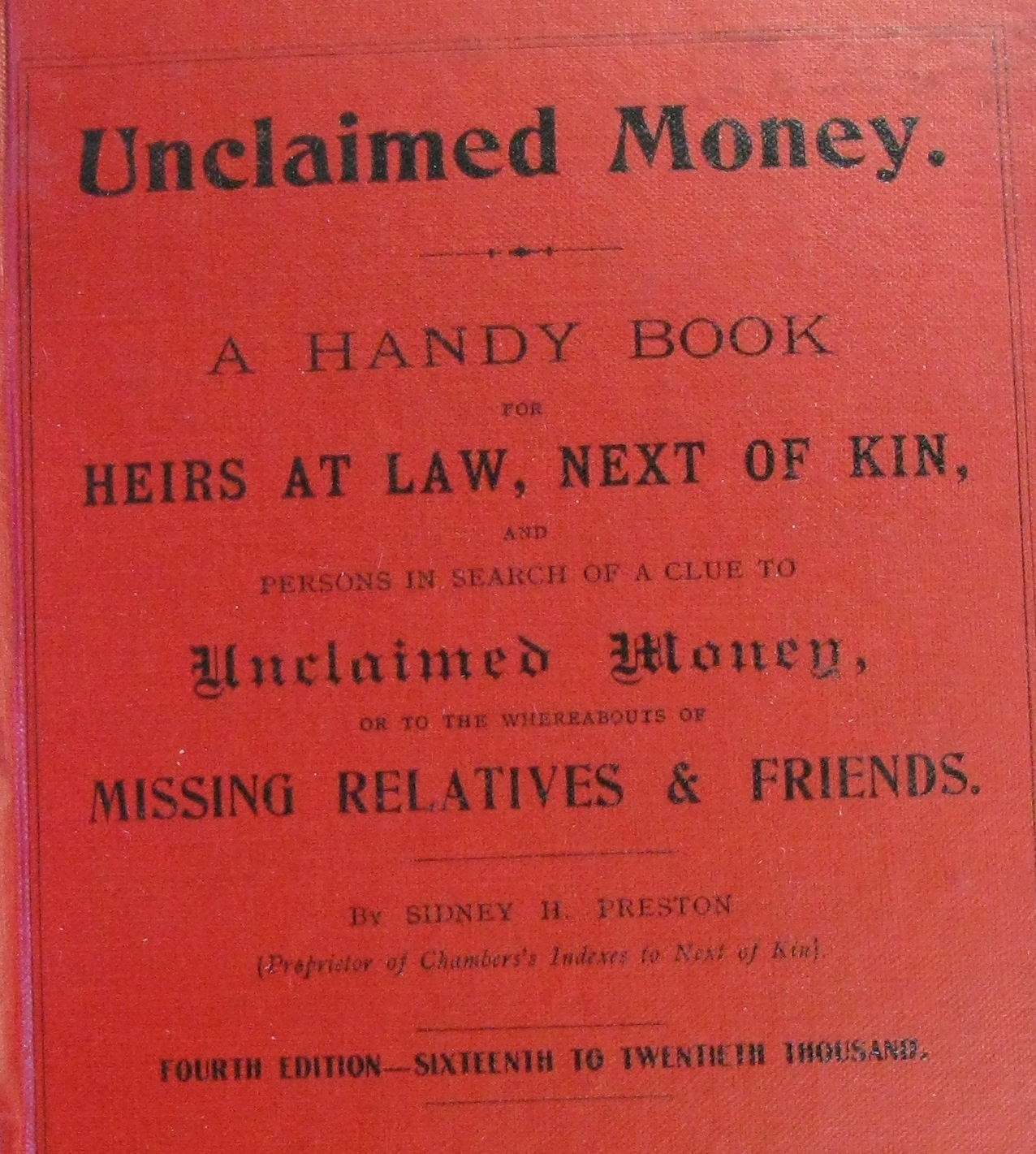

I assumed that the lack of stringent registers of people back then meant that more people could get lost far more easily but it appears that despite developments in advertising, claimable amounts continued to grow. By the end of the 19th century they were somewhere in the millions and the lists in the London Gazette ran up to 187 pages long. Sidney H. Preston in his book ‘Unclaimed money’ puts this down to “the extent of the British Empire, migratory and enterprising habits of the British population”. He argued that adverts were placed for a variety of reasons, because paper holders lost them under the influence of drink, or died with them undiscovered, that people were too scared to travel to make their claims (one family ‘lost heart at seeing the sea at Liverpool’) or that the persons involved in a case were so suspicious of each other that they refused to give out any information.

I assumed that the lack of stringent registers of people back then meant that more people could get lost far more easily but it appears that despite developments in advertising, claimable amounts continued to grow. By the end of the 19th century they were somewhere in the millions and the lists in the London Gazette ran up to 187 pages long. Sidney H. Preston in his book ‘Unclaimed money’ puts this down to “the extent of the British Empire, migratory and enterprising habits of the British population”. He argued that adverts were placed for a variety of reasons, because paper holders lost them under the influence of drink, or died with them undiscovered, that people were too scared to travel to make their claims (one family ‘lost heart at seeing the sea at Liverpool’) or that the persons involved in a case were so suspicious of each other that they refused to give out any information.

The potential of finding you were owed a fortune you didn’t know about was therefore real and while the lost person element was creepy, to those hoping to be found it was obviously quite thrilling: as the caption title of my book declares: ‘Chance is the salt of life, you may be one of the lucky ones!!’

These hopes were encouraged by stories of luck in the press: A 76 year old tube maker of Wednesbury was found to be the lawful heir of £60,000 which had been left to his father over 60 years ago. My favourite though is the story of a butcher in Sydney, Australia, who one day kissed one of his prettier customers. She resenting the affront promptly prosecuted him for assault. The attention of the press advertised his location to a firm of solicitors who had been looking for him for the last 19 years. And so he gained a significant inheritance due to his indiscretion.

tube maker of Wednesbury was found to be the lawful heir of £60,000 which had been left to his father over 60 years ago. My favourite though is the story of a butcher in Sydney, Australia, who one day kissed one of his prettier customers. She resenting the affront promptly prosecuted him for assault. The attention of the press advertised his location to a firm of solicitors who had been looking for him for the last 19 years. And so he gained a significant inheritance due to his indiscretion.

Missing heirs and unclaimed assets are still a big business today, TV programmes encourage it and numerous firms exist to help. I’m definitely not saying we should help out those sending the begging emails or in fact become them ourselves but maybe it would be in our best interest to stay visible on the off chance (but please not through kissing your clients, business partners or work colleagues).

Unclaimed money by Sidney H. Preston 1909.7.1920

Missing heirs and next-of-kin by News of the World 1912.7.1699

Wouldn’t it be nice if it were true and you did come into some money.