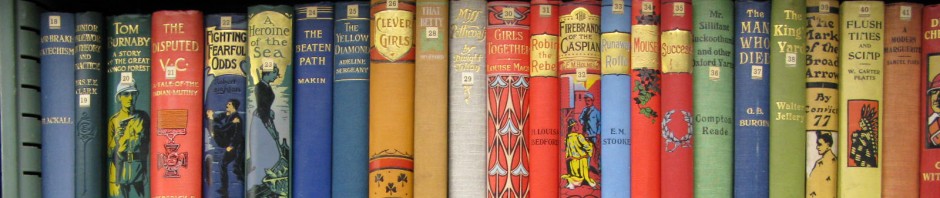

I want to jump back in time twice today: first let’s go back to 1944. John Betjeman was broadcasting to a war-time audience, and had in fact been asked to talk about how paper rationing was affecting publishing and reading habits. (The text of the broadcast can be found in the book pictured here: Trains and buttered toast.) Instead Betjeman encouraged people to re-read the older books thay already owned, launching into an enthusiastic review of his favourite Edwardian literature: the detective story Trent’s last case by E.C. Bentley and Red pottage by Mary Cholmondeley (about “family life and mental cruelty amid the lush and uncaring landscape of Shropshire”.) Betjeman listed his favourite Edwardian authors as: Miss S. Macnaughtan, Booth Tarkington, Q, Leonard Merrick. No, never heard of them. But read Betjeman’s talk and you may find, as I did, that you can’t wait to try them. Most striking is the way Betjeman can take you back to Edwardian times in a jump. Ready?

I want to jump back in time twice today: first let’s go back to 1944. John Betjeman was broadcasting to a war-time audience, and had in fact been asked to talk about how paper rationing was affecting publishing and reading habits. (The text of the broadcast can be found in the book pictured here: Trains and buttered toast.) Instead Betjeman encouraged people to re-read the older books thay already owned, launching into an enthusiastic review of his favourite Edwardian literature: the detective story Trent’s last case by E.C. Bentley and Red pottage by Mary Cholmondeley (about “family life and mental cruelty amid the lush and uncaring landscape of Shropshire”.) Betjeman listed his favourite Edwardian authors as: Miss S. Macnaughtan, Booth Tarkington, Q, Leonard Merrick. No, never heard of them. But read Betjeman’s talk and you may find, as I did, that you can’t wait to try them. Most striking is the way Betjeman can take you back to Edwardian times in a jump. Ready?

“Think yourself back into a time when elk horns were a feature of every large entrance hall and a flowered paper was a feature of every small one, when electric lights were in ‘pear shaped globes’ … and these books were on a shelf in the sitting room, small red-bound volumes, on good paper, in Nelson’s Sevenpenny editions”

I found it characteristic of Betjeman that he remembered the past in terms of light fittings and wallpaper. But what impressed me when reading Betjeman’s article was that all these Edwardian books had “second lives” for many years after they were published. They survived and were lent to friends, or sold at jumble sales until by 1944 they were still on many bookshelves, even if not often read. And now here we are in 2012, resurrecting them again. Interestingly, many are still flourishing: Trent’s last case has 41 reviews on the Good reads site. The dust-jacket of Trent’s last case temptingly describes it as “the best detective story of the century” (in 1913 the century had still some way to go) and I settled down to read it last month and enjoyed it very much. True, the pace of story-telling is slower than I’m used to, and the attitude to women almost as strange as Dickens’, but it’s a gripping mystery. You can see how it led Dorothy Sayers to create Peter Wimsey, with his eccentric manners and addiction to literary quotations. It’s inspired me to read other popular novels published around 1913 – and thus extend their lives even further.

I found it characteristic of Betjeman that he remembered the past in terms of light fittings and wallpaper. But what impressed me when reading Betjeman’s article was that all these Edwardian books had “second lives” for many years after they were published. They survived and were lent to friends, or sold at jumble sales until by 1944 they were still on many bookshelves, even if not often read. And now here we are in 2012, resurrecting them again. Interestingly, many are still flourishing: Trent’s last case has 41 reviews on the Good reads site. The dust-jacket of Trent’s last case temptingly describes it as “the best detective story of the century” (in 1913 the century had still some way to go) and I settled down to read it last month and enjoyed it very much. True, the pace of story-telling is slower than I’m used to, and the attitude to women almost as strange as Dickens’, but it’s a gripping mystery. You can see how it led Dorothy Sayers to create Peter Wimsey, with his eccentric manners and addiction to literary quotations. It’s inspired me to read other popular novels published around 1913 – and thus extend their lives even further.

Most of those authors are well represented in Newton, but not Miss S. Macnaughton. Who is she??

The only possibility I can see is “Macnaughton, Sarah Broom, d.1916.” She turns up a total of two books in COPAC:

So one of Betjeman’s favourites is only currently held in National Trust libraries? That seems unlikely. Who am I missing?

Mystery solved: her name was spelled as Macnaughton in the Betjeman reprint, but it fact her name is: Macnaughtan with an a. Which brings up lots of exciting possible reads on COPAC, including the intriguing title: The expensive Miss Du Cane. Who was she and why was she expensive?